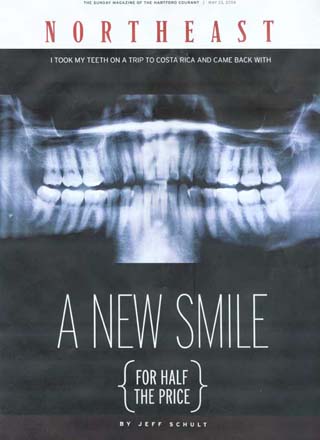

A New Smile (cont.)

(Page 5)

"Are you OK? Do you want to stop?" Telma asked a few hours later. "This would normally be three visits, what we are doing here."

I was, in fact, exhausted. But I wasn't in any pain. I had heard root canals could be agonizing, but I was more worried about the stamina of the dentist. Such precise work, for such a long time, so late in the day.

"Don't worry about me," she said, and went back to my root canals. We spoke infrequently that evening. It occurred to me how little I knew about dentistry and I decided that was, in part, because there is no way to ask questions, to be my normal, curious self, while the work is being done. Telma chatted occasionally but maintained intensity.

She finished the sixth root canal about 9:15 p.m. Josef was the only other person left in the office. We made an appointment for the next morning.

"You can sleep in a little; we will start at 9:30," Josef said.

Telma called Elke at Las Cumbres, who arranged for a cab to pick me up. The inn was mostly dark and behind a tall, closed gate when we pulled up. Elke opened the gate and paid the cab driver; part of her service is taking care of transportation. The cab driver spoke no English, and I was happy not to be figuring out the fare. I had no colones, the local currency, anyway. How could I? I'd had time to drop off my bags, have lunch and go to a seven-hour dental appointment.

Elke wanted to make me some dinner and gave me a mother's arched eyebrow when I declined; but my mouth was numb and my face hurt from keeping my jaw wide open for hours. I admired my accommodations - a sitting room with wicker furniture, fresh-cut flowers on the table, a kitchenette and a door leading to a small bedroom and a bathroom. I flicked through the cable TV channels - both English and Spanish. The Cartoon Network is hilarious in Spanish, at least to me, and "Dexter's Laboratory" was almost as comprehensible to me as it is in English, despite my not understanding a word. I figured out the alarm clock and fell dead asleep on the bed, fully dressed.

It had been quite a day.

I woke up before the alarm, surprisingly, and showered in a large stall, built for wheelchair access. It reminded me that most of the guests at Las Cumbres are there to recuperate from cosmetic surgery on their faces and bodies.

Outside, day dawning, I took photographs of San José, set against its mountains, before going to the dining room for breakfast. I had coffee and incredibly fresh fruit - melons, mangoes and guava - while checking my e-mail on a communal computer. Costa Rica has broadband. Though I heard many complaints about the government-run telecommunications company, Internet access was pretty good, better than I had expected. I was even able to use my Internet telephone service, Vonage, to make calls home to Connecticut for no charge. I told a friend about having six root canals in one evening.

"Now you must know what childbirth is like," she said. I considered letting her think so, but then said it had not been so bad - "Grueling, not painful," I described it. She was frankly disbelieving.

Other guests trickled in, some of whom I had met briefly the day before. I was currently the only male in residence at Las Cumbres, though that was not typical. Couples are common; husbands accompany their wives when they go to Costa Rica for cosmetic surgery, and, increasingly, men are cosmetic surgery patients, Elke said, when I later had a chance to talk to her at length.

"It is good that men are doing this," she said. "Women work hard to look good. Men can put in some effort." She was smiling, but I think she meant it. Elke is 58 and looked 15 years younger than that, to my eye. She has "had work done," to use the accepted euphemism.

I stayed at Las Cumbres just three nights and cannot recall being thrown together with a more pleasant collection of strangers. They called themselves "Elke's Kids," and Elke did not seem to mind taking them under her wing. Most of the women I met were in their 40s and 50s. They had no particular vanity about them, no obsession with youth. They simply wanted to look better, feel better about themselves.

I chatted with a few of them over breakfast. Sandy Talley from California was nearly recovered from her nips and tucks; she was contemplating having her teeth bleached - "Might as well do it while I'm here" - before heading home in a few days. Vicki Duncan, a self-described vagabond, wore dark glasses to cover the work done on her eyes. She is a U.S. citizen but had lived frugally but comfortably in a Costa Rican village for most of the past 11 years.

Nina, who asked that I not use her last name, looked like she had been in a car wreck. She had had a face lift, a neck lift, a "medium chemical peel" and perhaps some other "work" that did not make it into my notes. That night, she showed me the estimate she had from a cosmetic surgeon in New York City for the major procedures she had wanted. It came to $22,400 - $18,000 for the face and neck lift, $2,100 for an operating room fee, $1,320 for post-operative nursing care and $1,000 for anesthesia.

Her entire doctor bill in Costa Rica would come to $5,700, she said. She had gotten a good price. But that morning, she was wondering if she would ever again look anything like she had looked before, let alone better or younger.

Sandy said she would. Elke said she would. They had "been there, done that." I didn't have a clue, but I said I was sure it was going to come out fine, anyway.

At 9:30, I was on my back in the dental chair again, listening to Josef apologize for his English, which sounded fine to me. He numbed my mouth thoroughly and started sculpting my upper teeth, one by one. I encouraged him to talk as he worked, sometimes by making grotesque gurgling sounds, more often with a wave of the hand; and he warmed up and chatted easily about Costa Rica, to me, while maintaining a running dialogue in Spanish with his assistant.

Eight hours later, most of which Josef spent wielding dental tools inside my mouth, we were nearly done. I had felt him turn all my top teeth into fence posts with no crossbars, gapped by little stretches of gum. He had taken molds of what was left, and sent them to the lab. I looked and felt like an orc in "The Lord of the Rings" - pointy teeth, mouth flecked with putty and drool, no muscle control.

I knew early on that it was very much too late to turn back. But I had been doubting my wisdom and sanity in coming to this place for most of the day.

Josef held my temporary crowns - plastic teeth made from his molds in one hand as he touched them up, delicately, with the same whirling, whirring tools he had used in my mouth. He was utterly absorbed in his work, and I forgot about my real teeth for a few minutes as I watched him finish making the fake ones.

I commented on how happily intense he looked, and he smiled.

"Some dentists, maybe, would not take so much care with the temporaries," he said.

He admired them a moment more, and then it was time for me to "open" again. It took just a few minutes to cement these plastic teeth over the carved posts in my mouth.

It hurt even to try to smile, but I tried anyway, and looked in the mirror. My mouth - my whole face - was transformed. I had teeth!

"Don't kiss anyone too hard with these," Josef advised.

"I don't know anyone here so well that I would be kissing them."

He paused. "That is not a problem in this country," he said. We left it at that. I asked if my permanent crowns would look as good as the temporaries.

"Better, much better than this," said Telma, who had come into the room to admire the work. We made another appointment for the next day. My lower teeth needed some shaping and bleaching to match the final upper ones that would be made in the Prisma Dental lab over the next week, from the same molds that had been used to fashion my plastic smile.

"The hard work is over," Josef said.

The next day, Wednesday, was pretty easy. I felt incompetent to select the shade of white I wanted my teeth to be, which exasperated Telma a little. But I made her pick, anyway. Josef shaped my lower teeth a little and filled two tiny cavities I hadn't known I had. I donned dark glasses for one round of laser bleaching, which I wasn't sure I wanted but allowed to happen. My lower teeth needed to be whiter, still. I was given a mouthpiece fitted to my lower teeth and a bleaching gel in syringes.

Telma helped me find a place to stay for the following night, the Quality Hotel in San José, about a 20-minute walk from the Prisma office. I was reluctant to leave the comfort and familiarity of Las Cumbres, but I also wanted to save a few dollars and was anxious to see Costa Rica from the ground. It is absolutely possible to go to Costa Rica for cosmetic surgery or dentistry and entirely avoid any real or imagined dangers or inconveniences - places like Las Cumbres make that easy to do - but I wanted to see San José and some of Costa Rica on my own.

On Thursday, I said my goodbyes at Las Cumbres and Elke herself gave me a ride downtown to the Quality Hotel in the Central Colón area. I considered it a big favor; I would have taken a cab, but she said she was happy to do it. She waited while I checked in and then drove me to the dentists' office. I said I would stop and see her before I left the country, and I meant it; and she told me to stop by for dinner. She is a friend, I think. I am sure many, even most, of those who have stayed at Las Cumbres over the years feel the same.

In the office, Telma inspected my lower teeth. "Much whiter, much better!" she said. We sat for a while, the same office where three days earlier she had delivered the bad news about the condition of my teeth and the expense to refurbish my mouth. It was only 5 p.m., several hours before her day would end. She had not had lunch. I told her that she and Josef worked "like dogs," a colloquialism that I was nonetheless sure she would understand, and she did.

From Josef, I knew they were both born in 1958, making them just two years younger than me and not 10, as I had guessed at first. Telma said they went to kindergarten together, which made them childhood sweethearts going back further than any I have ever encountered. They had gone through Costa Rican schools and university, to graduate school in Switzerland, to advanced training in the United States, together. For 16 years, Telma had taught at a Costa Rican University and Josef had worked as a dentist in the country's public health system while they built Prisma Dental on the side.

I had thought that, perhaps, their enterprise had been supported in some way by the government of Costa Rica. I had found websites claiming some government affiliation or sponsorship of health tourism, for the doctors and dentists with private practices who sought clients overseas. I asked about that.

She looked at me evenly. "We built this, Josef and I," she said simply. They had moved into these new offices, housing their practice, lab and dental supply business, just five months earlier.

It was worth it, she said, but there had been many sacrifices along the way. There had not been as much time for their two daughters, now teenagers, as she would have liked. Building a business with her marriage partner had also had its difficulties.

"We are both very competitive," she said. "Even with each other ... you learn to let the other person lead, sometimes." She feared that the workload had dulled her creative edge.

"I would like to do other things. I would like to be more involved in the marketing. But there is no time," Telma said. "Sometimes I feel like an automaton. The work is everything."

She asked if I would like to have dinner with her and Josef the next night, Friday; also, if I would like to go out with some of the office staff on Monday evening. I was surprised, and said so.

She smiled. "We go out with our patients, if we like them," she said. "You are a friend. The girls like you, too. They would not invite you otherwise."

Page(s) 1 ... 2 ...3 ... 4 ... 5 ...6 ... Next ...

Page(s) 1 ... 2 ...3 ... 4 ... 5 ...6 ...7...

For more information on traveling outside the country for medical care, see: Beauty from Afar

... and if you like this article, you might also like my blog at: www.jeffschult.com.

Prisma does all their own lab work on the premises so I got to watch Roman, above, and Yorleny, below, work on my new teeth.

Photos by Jeff Schult .

Nina, right, stayed at Las Cumbres Inn, San Jose, for about 12 days while recovering from cosmetic surgery -- she had a facelift, necklift and a chemical peel. Elke Arends, left, is the unabashed "mom" and mistress of Las Cumbres, a 10-room inn and "surgical retreat" that caters primarily to "health tourists" who travel to Costa Rica for cosmetic or other elective surgery. Arends encourages her guests to bond, talk and help each other, believing that the support patients give each other is an important part of the recovery process.

The Butterflies of La Paz (story, photos)

Home and Abroad: Comparative Cost Chart

Las Cumbres Inn/Surgical Retreat